This is an interlude in the worm simulation series because of something I realized about my last post, Why I don’t want worms in my computers.

During my PhD at Harvard and my postdoc at UCL, I went through formal peer review with some of the highest impact factor-publications out there. I’ve acted on both ends of the process, either as reviewer or reviewee. And my conclusion is that peer review doesn’t work.

How come?

Reviews are maddeningly inconsistent

A student in a lab I was in—let’s call them R—announced one day that “reviews are completely stochastic.”

R had submitted a paper to a very competitive venue and gotten rejected. But R disagreed with the reviews, and simply switched the order of two sentences before resubmitting to a different, equally prestigious venue. Where it was accepted.

In a separate incident, a different student sent a manuscript to a high-impact place and got back two reviews. One of them said something like,

Hot damn, this will be a foundational paper in the field.

The other said,

This is dumb and nothing new.

(I paraphrased.)

What then?

And it’s not just opinions that are inconsistent—you also have no clue who reviewers are. Reviews are blind, which is good for preventing bias, but it also means that sometimes you’re being reviewed by the singular expert in the field, and other times your career hopes rest on an undergrad who got your paper pushed onto them by a postdoc who suddenly got too busy to do it themselves.

Usually the second one.

Reviews can take so long that you’ve forgotten about the project, or so long that somebody dies.

(The last thing really happened to someone I know.)

In my experience, it takes a minimum of three months for first reviews to get back to you. Later rounds can add up to well over a year. And that’s only if you get accepted—otherwise, you resubmit and start over. So for multiple rounds of submission, review, and rejection, it can be several years before publication.

A lot can happen in that time. You can graduate from college; you can graduate from your PhD. You can decide to change research directions altogether.

All of these applied to me at some point—by the time reviews came back, I didn’t remember the details of my project anymore, which were, as it happens, exactly what I needed to address reviews.

Also, I was normally less invested by then. Instead of trying to improve the paper, I’d want to get responses done as fast as possible so I could work on a new thing.

Overall, the peer review is not a good system for good science. For deeper discussions on the messed-up reality of peer review, see:

The present and future of peer review: Ideas, interventions, and evidence (Aczel et al. 2025, PNAS)

The misalignment of incentives in academic publishing and implications for journal reform (Trueblood et al. 2025, PNAS)

Adam Mastroianni’s post, linked below.

More or less, the consensus is that peer review (1) controls how science is done today and (2) is kind of hot garbage. Formal peer review lets a handful of anonymous reviews of highly variable quality decide where your career goes next, and

that’s

just

how

it

is.

But Substack comments have been cool so far

I’ve been surprised by the amount of engagement on my posts.

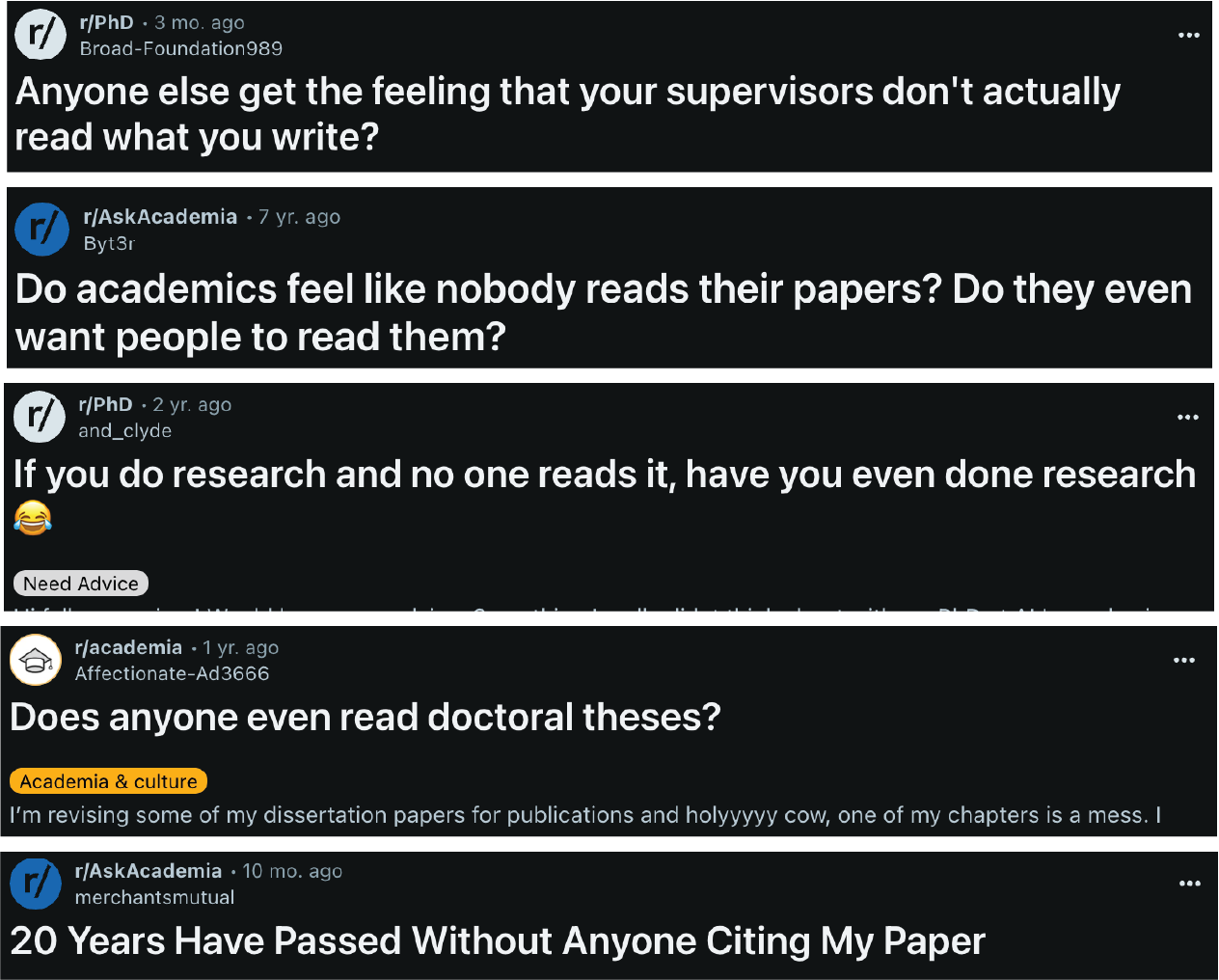

I had probably less than twelve readers for my undergraduate, master’s, and PhD theses combined, so that’s where my bar is. My readership wasn’t a reflection of the quality of my work, either (is what I’m telling myself); most scientists get used to this lack of attention.

But on my last post, readers did pay attention. And they gave me a lot to think about. Specifically, they made me think I could have written the essay better, and for the last week I’ve been asking myself,

How could I have sharpened my arguments?

Are they right—were my analogies not good analogies?

And to my embarrassment, I wrote this nonsense to someone in a comment thread:

My plan for future posts is to lay out the stuff I've been working on […] (so maybe I'll address your questions eventually!). If you're curious now, though, unfortunately all I can do is refer you to my PhD thesis.

This is a two-for-one copout (although the person I wrote this to was quite gracious about it).

I effectively said, I’ll get to it later, and in the meantime, here’s 200 pages of reading for you to do. It’s like writing that something is “out of the scope of this paper”—it could be true, but it could also just be lazy.

Which means I’m going to try something new: I’m going to use Substack as an alternative to formal peer review.1

Here’s how I’ll do it

(but feel free to give me suggestions)

Every once in a while, if

I feel a post isn’t good enough based on feedback, and

I really care about making those ideas clear,

then I’ll go back and revise. I’ll try to improve my arguments, or change them if you’ve changed my mind.

In the last few posts I’ve been setting context for my current work, which is on understanding and building small natural intelligences. But soon I’ll be writing up actual data, with code, which means that future revisions won’t just be to presentation but to the work itself.

For a given post there might be no revisions, or there might be several. I’ll announce them with a Note (Substack’s version of tweets, I guess) instead of spamming people’s inboxes; I’ll also explain what prompted the changes.

And I won’t remove the drafts. I want to keep old discussion threads and the stuff being discussed. But I will put junked drafts behind paywalls to separate them from edited versions. So if you’re a paid subscriber, thank you so much for your support! You’ll get (/win) permanent access to my Substack landfill—vague points I failed to make, uncomfortable jokes that didn’t land, and detailed comment sections pointing out my flaws.

Here’s why I think it can work:

1. Feedback is fast

Within days, I can have a whole back-and-forth with readers about what I’ve written. I can have DM exchanges to find out why people are interested and what they want to hear more about, which might surprise me.

Best of all, these exchanges happen while I still remember what I meant by a particular sentence.

2. Comments have already been really good

“A blog post is a very long and complex search query to find fascinating people and make them route interesting stuff to your inbox.”

Since I started writing, I’ve learned at least two important things from readers:

There’s a team in New York working on the worm simulation problem, following Moore et al. 2024 which models neurons as “data-driven controllers” (thanks to Nicolas R for mentioning it). Brief thoughts from me in the footnote.2

My understanding of the brain aligns with Philip Ball’s thoughts on genetics, especially when it comes to biological emergence and agency.

Philip Ball is a science writer and former editor at Nature who published a book titled How Life Works in 2023. Check it out, and thanks to ozzie for recommending (see the footnote for a teaser3).

3. You guys are reading this in your free time

Lots of reviewers just don’t care much.

Editors assign them papers (although they can decline) and then they do their academic community service. Some reviewers are meticulous and do care, but I’ve found these uncommon.

In contrast, Wikipedia is existence proof that people critiquing stuff in their free time can be incredibly good for accuracy.

Don’t Meet Your Heroes

Or, how Randy Pausch became a contributor to the World Book

Randy Pausch was a professor in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University from 1997 to 2007. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2006, and when he had a few months to live, he gave a final lecture at the university titled, “Really Achieving Your Childhood Dreams.” The lecture was extended into a now-famous book, The Last Lecture.

In Chapter 8, Randy talked about how he used to dream of contributing to the World Book Encyclopedia. The World Book was one of his favorite things as a kid.

Then Randy grew up for a few decades. He got a PhD in computer science; he got a tenure-track job. And that’s how Randy found himself in the position to finally achieve his childhood dream. As in, he was

important enough to have his expertise recognized,

but not so important that the World Book staff thought he’d be busy when they called him.

An excerpt from The Last Lecture:

But it’s not like you can call World Book headquarters in Chicago and suggest yourself. The World Book has to find you.

A few years ago, believe it or not, the call finally came.

[…] “Would you like to write our new entry on virtual reality?” they asked.

I couldn’t tell them that I’d been waiting all my life for this call. All I could say was, “Yes, of course!” I wrote the entry. And I included a photo of my student Caitlin Kelleher wearing a virtual reality headset.

No editor ever questioned what I wrote, but I assume that’s the World Book way. They pick an expert and trust that the expert won’t abuse the privilege.

I have not bought the latest set of World Books. In fact, having been selected to be an author in the World Book, I now believe that Wikipedia is a perfectly fine source for your information, because I know what the quality control is for real encyclopedias.4

Pausch, Randy; Jeffrey Zaslow. The Last Lecture (p. 42). Hachette Books. Kindle Edition.

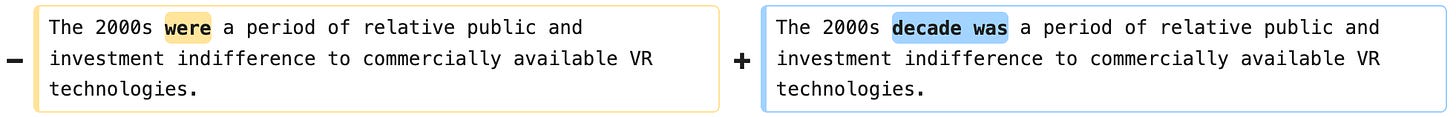

In case you’re curious, there have been more than 50 edits to the Wikipedia page on virtual reality (VR) in the last seven months (since January 2025). Here’s one of them.

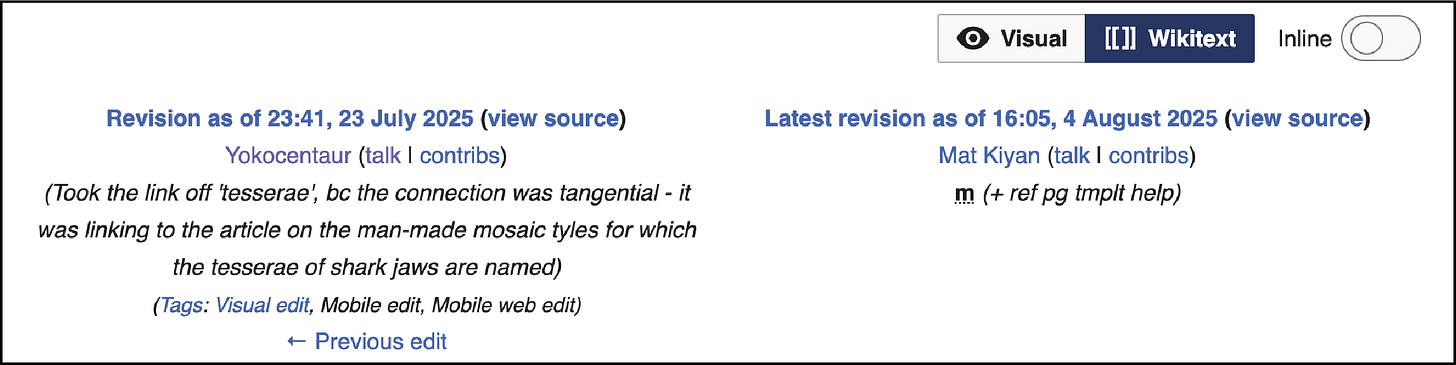

Except VR has been in the zeitgeist lately, so maybe it’s not a fair comparison. Let’s look at the page for sharks instead. Sharks have not changed much in the last million years. That hasn’t stopped people from making over 100 revisions to their page, also since January.

Here’s one from two weeks ago.

To conclude this section, this is a story in favor of Wikipedia from my own life (albeit less poignant than Randy Pausch’s).

Back in 2019, a friend made a Wiki page for another friend for his birthday. I’ll call the second friend Anthony. Anthony’s birthday present got taken down within ten minutes because he wasn’t important enough.

I was quite impressed by this—it was totally the right move, since Anthony didn’t have any Wikipedia-level accomplishments to his name. (Sorry Anthony—you don’t have any Wikipedia-level accomplishments to your name yet).

I’m not saying my personal blog is going to be the rigorous gauntlet that is Wikipedia. But I do think it’ll be better than formal peer review.

4. There aren’t dumb incentives

Peer review, while nice in principle, is warped by a Goodharted system of rewards.5 Scientists have to publish their work, so they’ll do whatever they can to convince editors and appease reviewers.

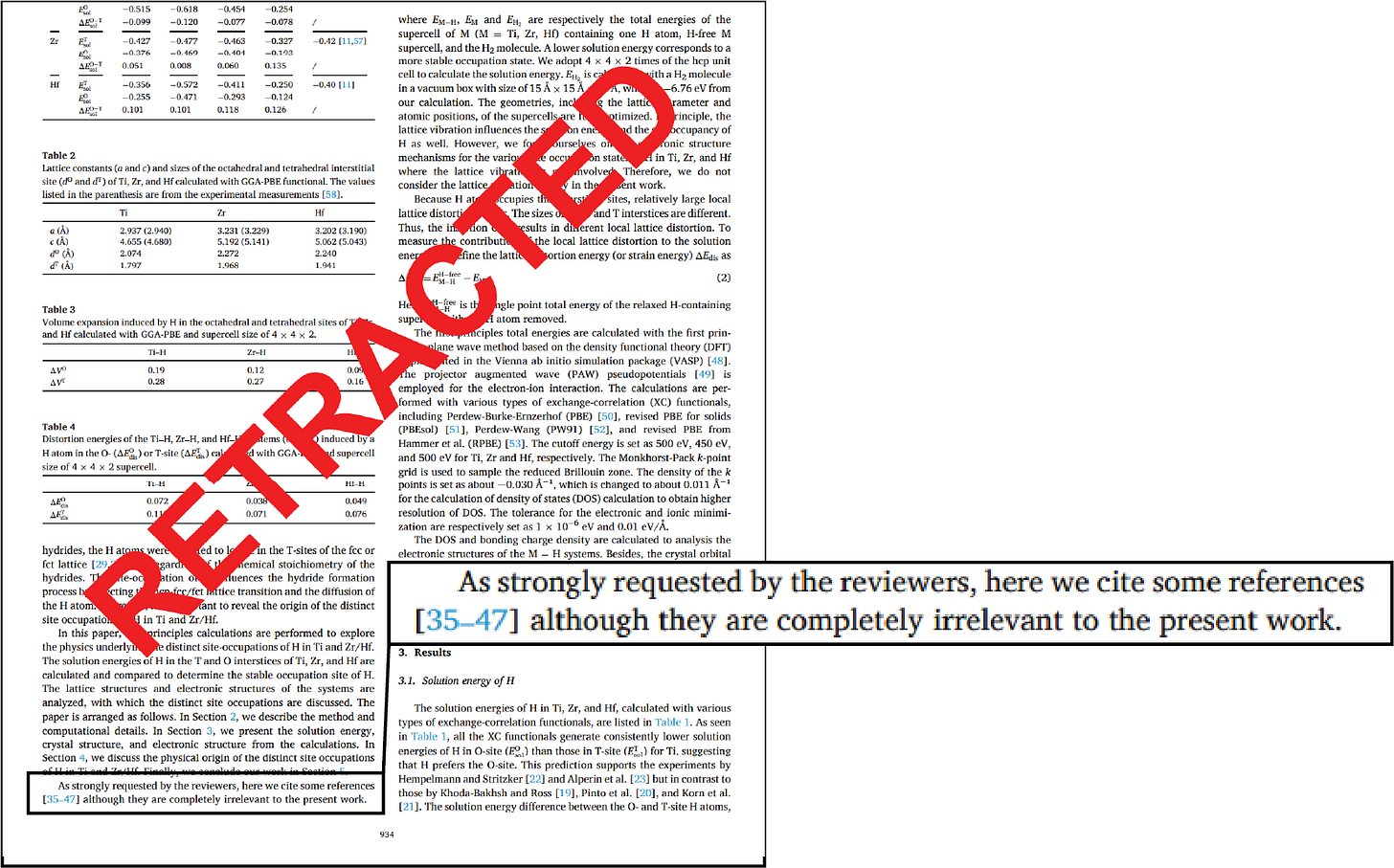

Sometimes this means adding unnecessary data that clutters up the story. Other times it means adding unnecessary citations, like in the example below. Reviewers boost their own citation counts like this pretty often, though there’s rarely so much drama about it.

But you don’t benefit from quashing my ideas on some random blog and I don’t benefit from brownnosing. Egos aside, I think we both want my writing to be better and for me to fix it if it’s wrong.

You might think, but wait, can’t you just not listen if you don’t want to?

Yes, and I think that’s a good thing.

Consider Pixar’s “Braintrust”

Ed Catmull, the co-founder of Pixar, touted the Braintrust as one of Pixar’s best practices in his memoir Creativity, Inc.6

The Braintrust was a sort of master review committee that came out of Toy Story, and the whole idea was that it was a committee with no authority.

A director would present a work in progress and the Braintrust would give feedback. “This is crucial”, wrote Catmull. “The director does not have to follow any of the specific suggestions given. After a Braintrust meeting, it is up to him or her to figure out how to address the feedback.

“To set up a healthy feedback system,” he said, “you must remove power dynamics from the equation—you must enable yourself, in other words, to focus on the problem, not the person” (emphasis mine).

This is vastly different from peer review, where reviewers and editors have all the power, and the burden is on scientists to convince the all-powerful of how their work should be written.

And while Pixar is about art, and science is about truth, I think there’s a lot of overlap in how to get the best versions of both.

Counterargument: but shouldn’t experts be the ones reviewing science?

Formal expertise is good. It’s worth noting that the first Braintrust was made up of only storytelling legends (e.g. the directors of Toy Story, Finding Nemo, Cars, Wall-E). And being in “the system” for the last ten years has taught me basically everything I know; you learn a lot being around experts who are thinking intensively about the same problems you are.

But things could be better.

Like, I don’t like how experts can be hyperspecialized—people are way too focused on way too specific areas of science. I think hyperspecialization is helpful when we already have a decent picture of a field and are trying to fill in details, but neuroscience is definitely not there yet.

So I’ll take any help I can get. I want to hear from neuroscientists outside my building, scientists from other disciplines, and from people who read this stuff in their free time.

Plus, this is still my blog. I get to decide which comments to listen to. If you’re an expert who disagrees with me, let me know. Then write it on your own blog.

To summarize,

A few months ago, I learned about Adam Mastroianni, whom I cited earlier. Adam is a psychologist who stopped playing the academia game and has been publishing his work on Substack instead.

Not to be creepy about it, but I think his life is really cool and I want to copy a lot of it. Except I’m not a psychologist; I’m a computational neuroscientist who hopes that by posting here, getting feedback, and revising, the work will be better. And that it will reach more people than if I did things the usual way.

Hence my experiment: can Substack be a better version of peer review?

(A simultaneous experiment: Can I write a blog that people will keep reading? Subscribe to find out.

And I am revising my last post. Out within two weeks.)

Of course, Substack isn’t formal peer review, because there’s no academia-approved publication at the end of it.

But I’ll use what I learn here to write better research papers. And if the review process and science writing culture make the ideas less readable, they’ll still be here in blog form.

I’m slightly more optimistic this approach will work compared to previous ones, because these neurons operate in a way that makes sense to me. I have reservations, though, because the authors’ arguments are from a normative perspective, and just because something aligns with one’s normative perspective doesn’t mean that’s how it works in reality (especially in biology). So I expect that at minimum, there will be extensive tuning required to get this idea to work.

Regardless, we’ll find out what happens. I’m glad someone’s still trying.

A quote from the prologue:

Yet misleading metaphors for the genome remain as persistent and popular as ever. The “blueprint” is a favorite, implying that there is a plan of the human body within this three-billion-character string of “code,” if only we knew how to parse it. Indeed, the whole notion of a “code” suggests that the genome is akin to a computer program, a kind of cryptic algorithm that life enacts…

But the key point is that looking to the genome for an account of how life works is rather like (this simile is imperfect too) looking to a dictionary to understand how literature works.

Ball, Philip. How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology (p. 3). University of Chicago Press. Kindle Edition.

The rest of the book throws piles of evidence at you to support this claim.

Although my opinions are backed by much less professional experience, I think the brain suffers from the same metaphor problem. Instead of the genome acting as a blueprint for how life works, it’s connectomes that are circuit diagrams for the computer of natural intelligence.

In the blueprint/circuit view, each part of the genome/connectome is supposed to have a fixed role, sculpted by evolution. This protein causes Alzheimer’s when there’s too much of it; this part of the brain does arithmetic.

But neither statement comes close to capturing the data. In the case of the brain, this conundrum inspired a two-day-long workshop at the largest annual conference in computational neuroscience in 2022 called, Why is everything everywhere? (Organizers: Evan Schaffer, Sue Ann Koay, Philip Coen, Florencia Iacaruso.)

Nevertheless, Randy Pausch still loved the World Book. Here’s how he ended the chapter.

But sometimes when I’m in a library with the kids, I still can’t resist looking under “V” (“Virtual Reality” by yours truly) and letting them have a look. Their dad made it.

Pausch, Randy; Jeffrey Zaslow. The Last Lecture (p. 42). Hachette Books. Kindle Edition.

Goodhart’s Law is that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” It’s based on work by the economist Charles Goodhart from 1975, and people use it in lots of contexts, e.g. economics, education, science, or reward-hacking problems in AI.

Catmull, Ed; Wallace, Amy. Creativity, Inc. (The Expanded Edition): Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

I think people underestimate how good feedback from non domain experts can be. They’re usually free from the kinds of assumptions everyone in your field already makes, meaning they will just ask the “dumb” questions. And personally, I’ve been surprised by how many supposedly dumb questions I struggle to answer, and they tend to further solidify my foundations by thinking through them.

Here me out: move peer reviews to github

I’m confident it addresses literally every issue (pun intended) you list